Thank You. I Love You. I Forgive You. Please Forgive Me.

What might emotional technology look like?

When I was in college, I volunteered for a few years at a crisis hotline. The phone lines were staffed almost exclusively by college students, most of whom had no experience in social work, psychology, or really anything useful for talking to someone at 1:30am who is really going through it.

The training program wasn’t a drawn-out affair: I think a night a week over the course of a couple of months. I remember being completely terrified.

They walked us through emergency procedures, how to look up local social services, and otherwise point certain situations in the most-useful directions. But mostly, it was a crash-course in how to listen to people.

Ours was not to council. It was not to give advice. It wasn’t to say things are going to get better. It was, mostly, to affirm. “That sounds really hard.” “It sounds like that makes you really scared.” “I can definitely understand why you are feeling sad.”

It was (and perhaps still called) reflective listening. And it was my single most-powerful tool in getting through a Friday overnight shift or a Tuesday sunrise stint. I’ve never really known what to call it: “technique” seems too clinical, and “skill” doesn’t capture its wonderful simplicity. It served me extremely well in my future teaching career, and I still have it at the ready at home and at work.

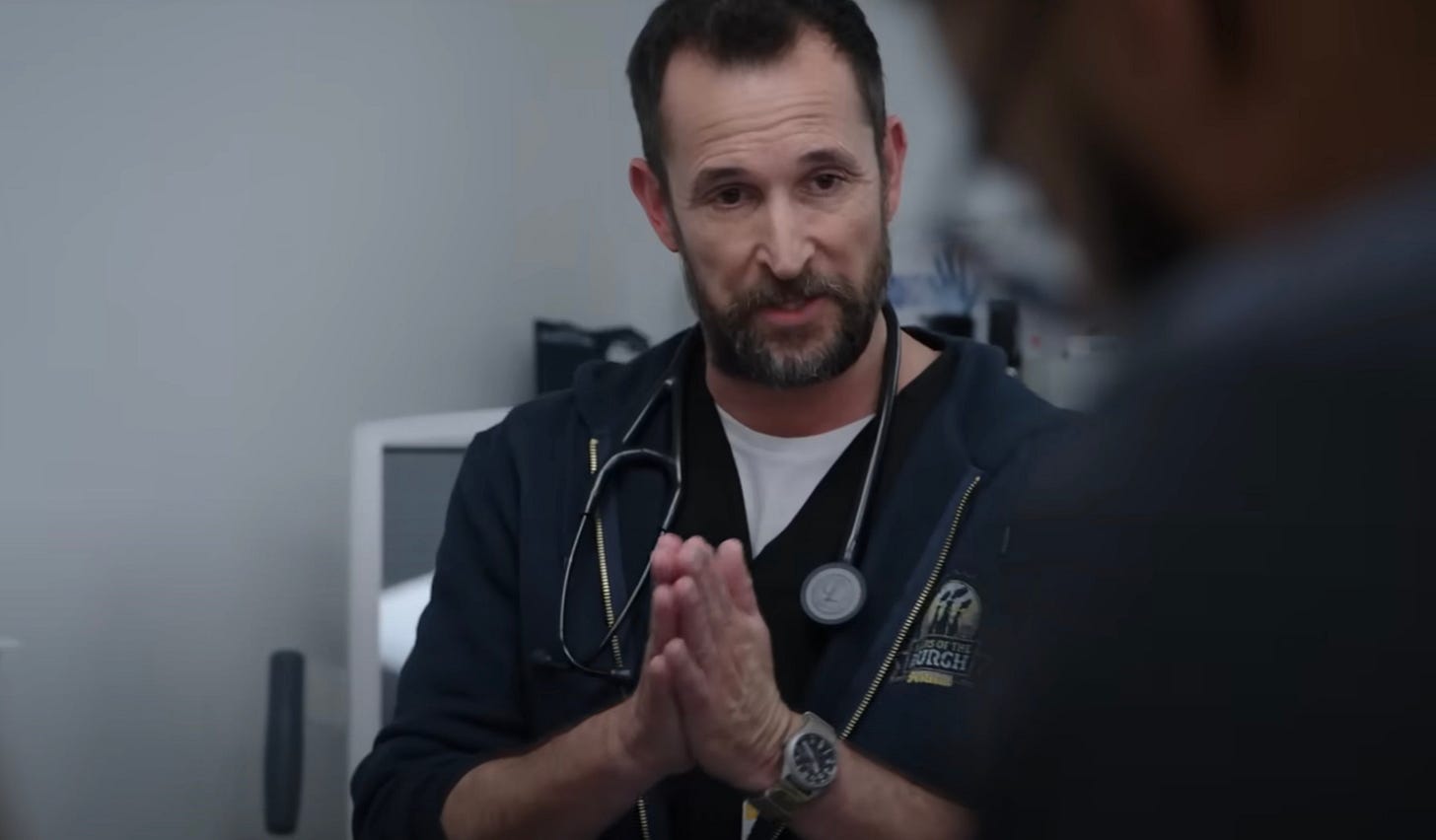

I was thinking of reflective listening while watching The Pitt a few weeks ago. The Pitt is a lightly-camouflaged setting and spiritual successor to ER, to the point that Noah Wyle is again a central figure (I have been recommended the series to friends as “ER, perfected”).

A key difference between them is that The Pitt takes place, all fifteen episodes, over the course of a single shift in the emergency room. The most potent consequence of this is that you spend more time with the patients. Very few real-life trips to the emergency room take less than a few hours, and in The Pitt, you follow a person, couple, or family through their whole experience.

A couple of cases anchor the early episodes, and the climax of one family’s story happens in episode four. An adult brother and sister have come in with their elderly and ailing father, who has reached the end of his life. After struggling through the previous episodes with the wrenching decision/realization that keeping him on a breathing tube is neither helpful nor humane, they decide to let him go. They then find themselves in the terrestrial purgatory of knowing he is going to die, but not when.

With little time to process, let alone reconcile with, what is happening, they are in crisis of their own. At this point, Dr. Robby (Noah Wyle, in a truly remarkable performance) asks if they are religious, knowing that this would be the moment to call upon whatever faith or ritual they might have. When the daughter responds, “Oh god no. No god,” Robby offers them something:

ROBBY: I had a teacher, mentor, who told me about a Hawaiian ritual called Ho'oponopono. Or, the four things that matter most. It’s just basically a few key things we can say when we’re saying goodbye to a loved one that can really help, at the early stages of loss.

ADULT SON: What are they?

ROBBY: They’re gonna sound really simple, but I swear I’ve seen them work.

ADULT SON: Okay.

ROBBY: I love you. Thank you. I forgive you. Please forgive me.

ADULT SON: That’s…that’s it?

ROBBY: Yea. I told you it was simple.

I won’t recount precisely how things unfold from here, but I will say that their use of Ho'oponopono allows them to access something they needed to.

I admit I am always more than a little suspect of neat, decontextualized deployments of cultural and religious practice, especially in popular entertainment. In this case, though, that it is a Hawaiian ritual is less important than that it works. From the moment Robby recited the four things, I knew I would be thinking about them for a long time—and most likely using them.

Reading a little more about Ho'oponopono added rather than detracted from my appreciation of its deep, human elegance. Ho'oponopono roughly translates as “to make right”: “pono” itself means “right or balanced,” so the repetition of “pono” after “ho’o” (to make), emphasizes that this is the deepest kind of right that can be made. Ho'oponopono as practice can sometimes be a part of mourning, but more often it’s a structure for conflict-resolution and reconciliation. The four things are said by both parties, usually under the supervision of an elder, as a path towards figuring whatever it is out. It precedes resolution by making mutual accountability, appreciation, and forgiveness openly stated preconditions.

The other piece of this scene that I have been thinking about is how Robby came to know about Ho'oponopono. He doesn’t learn about it through the formal, highly regimented process of medical education. Instead it comes in sort of sideways from his teacher, who in this moment he is quick to also call a mentor, presumably in a moment much like this one.

And what is the moment? It is immediate, acute, and a matter not of medical treatment but human feeling. It is not presented as a cure for grief. Instead, it is something to do right at this moment, “in the early stage of loss.” This anticipates future stages of grief for which Ho'oponopono perhaps is less effective, but right now, it fills the need at hand. It is a suture for the soul, providing just enough structure to allow longer-term, more fundamental, healing to take place. And it is not hypothetical—this is something that Robby says he has seen help people. It might be largely unexplained and unfamiliar, but the results makes that immaterial. This thing works.

It seems to me things like Ho'oponopono and reflective listening should be as well-known and practiced as splints or Advil or scissors or internal combustion engines. But they aren’t. The reasons why are as simple as they are frustrating. You cannot mass produce, package, and sell reflective listening. Ho'oponopono is not patentable, and it’s effectiveness isn’t something that will show up in a blood test or EKG. These practices do not possess the material qualities we have come to associate with the word technology, but they are products of human understanding, developed over time to address human needs. That the needs they serve are that of the psyche and soul, rather than the atom or electron, mask their power and and potential.

These emotional technologies are all around us. In AA meetings and after-school programs, in coaching and counseling, in negotiations and networking. We have a patchwork taxonomy for people who somehow have learned to use emotional technology in the form of “personality hires,” doctors who have great “bedside manner,” friends and co-workers with high “emotional intelligence” or excellent “interpersonal skills.” People who are, in the strangely useful formulation, a “people person.” These labels are describing the same thing: people using emotional technologies consistently and effectively.

What, then, would a high-school course in emotional technology look like? How extremely useful, and I am not kidding about this, would an employee with a doctorate in emotional technology be? What discovery might warrant a Nobel Prize in Emotional Technology? After all, what higher science can there be than the mastery of the condition of being humans together?

I’m going to be thinking of them and applying these four statements often. How powerful! Thank you.